Community Report - Initial Impressions

There were many more surprises in store for us during the first few weeks. We had, as I said, come expecting a few unpleasantnesses during an initial 'settling in' period. As I also said, however, these surprises affected us regardless of our forewarnings.

It is difficult to describe exactly what 'culture shock' is, but we all experienced it to varying degrees during our first weeks in Sri Lanka. When your surroundings are as alien to you as ours were to us at first, they often feel a lot more threatening and bizarre than they in fact are. The phrase 'fear of the unknown' perhaps explains this; it's easy when you don't understand something you witness to be suspicious of it.

I was not initially impressed with Colombo. Probably the first observation of it I made was how dirty it seemed in comparison to the British and European cities and towns I was used to. There seemed to be an immense quantity of rubbish in the streets, making pavements seem almost hazardous. The accompanying smells, combined with other powerful aromas, from exhaust fumes to pungent foods, made quite an assault on my sense of smell. Then there were the people. Sri Lankan people, whether Sinhalese, Tamil or of various other descents, look very different to the normal British 'faces in the crowd' which I was used to, they act differently and talk differently. It was perhaps not apparent to us initially how commonly English is spoken in Colombo, what we rather noticed was how often people speak in other languages. With no previous knowledge of Arabic, Tamil and most importantly Sinhala, it seemed a great majority of what was said around us, and even to us, was in a very strange and incomprehensible dialect. Foreigners are approached quite frequently in Colombo, whether by children beggars or seemingly friendly men in shirts and trousers. Even although these ambassadors almost exclusively speak in English, albeit not often with a great degree of accuracy or fluency, the strangeness of the encounter seemed a lot more sinister during those first few weeks than it would do once we were more settled in.

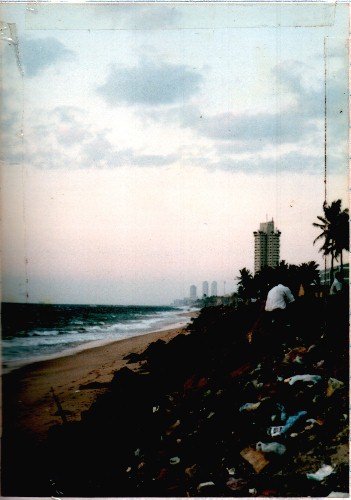

On an afternoon that we had free during our first week in Sri Lanka, a few of the new volunteers strolled around one of the more presentable areas of Colombo. I felt it very difficult to relax anywhere amidst the noise and bustle. To have a rest from our tentative exploring, we bought a few bottles of soft drink from a small roadside shop, not sure if we were to haggle or not when the shopkeeper explained to us in broken English, that we had to pay a refundable deposit on the glass bottles. We took these drinks, which were - as we were told - 'no cool', in the absence of a fridge in the shop, and tried to walk to the seafront, as we were on the main Galle Road which runs parallel to the coast. Doing our best to be nonchalantly cool as we awkwardly made our way towards our destination, we were plagued by a group of knee-high beggars. The sea came into sight, but it was with some disappointment we realised that there was no picturesque beach awaiting us, rather a heavily littered railway track. There was some sand between us and the Indian Ocean, but despite our thorough course of inoculations, we had little confidence that we could advance much further than the rusty tracks, without endangering our health. We stood pensively sipping from our refundable bottles, while the sea breeze blew warm mist into our faces, and carried dubious smells to our besieged nostrils. There was a common feeling that we were looking forwards to getting away from the city, and escaping to our projects in quieter, rural areas.

'On the beach' looking north towards the tall towers of Colombo's Fort district.

After our first few days in Colombo, we were collected by the various organisations we were working with for the year, and driven to our respective postings. I was eager to get to the training centre, where Giles and I were to live and work for our stay in Sri Lanka. The unfamiliar feeling I experienced in Colombo made me enthusiastic to start settling in as soon as possible. I felt sure that once we had the chance to 'put some roots down' we would begin to feel more at home in our new surroundings.

My first view of Batangala was as we drove through the gates, and up the path to the main centre, crossing paddy fields surrounded by tall palm trees bearing bright orange king-coconuts. It looked simply stunning.

Unfortunately, my initial feelings of enchantment were soon to be dispelled. Within an hour of being dropped at the centre, Giles and I sat alone in a small staff dining room, with our lunch before us. The fantasies we may have entertained about living on Sainsbury's-style chicken tikka for a year were about to be shattered. Among the delicacies on offer was a dish containing small dried fish, floating in a dark blood-red sauce. The smell issued forth by the dryfish annihilated any feelings of hunger in both of us. I was fairly horrified to find that even the plain white rice smelt extremely dubious. I later came to recognise this aroma as being distinctly similar to the smell of the paddy fields themselves and the waterbuffalow dung used to fertilise them. At the time, however, I only recognised the fact that the meal really didn't seem fit for human consumption. Nevertheless, Giles and I helped ourselves to the smallest amount of each dish that we thought seemed polite. We thought determined thoughts, and began our lunch. I hadn't particularly liked eating with my hands when we practiced it on Coll during training, but while eating that first meal, I was more concerned about touching it with my mouth. I think that it was the first time I had been forced to consciously run through the mechanical process of chewing and swallowing food. Perhaps my brain didn't recognise my mouth's content as food, and therefore failed to issue the appropriate instructions.

We were made to feel still less comfortable by the small crowd of male students staring at us eating through the door and windows of the room. Midway through our meal, we were joined by a further member of staff. He sat down to eat, and introduced himself to us as Mr Jayasiri, in an interesting version of the English language. This man's broad beaming grin, which was soon to earn him the nickname 'Smiler', did little to set me at ease.

When we had swallowed the last of the lunch, Smiler showed us to our living quarters. Some of the curious students carried our heavy luggage, refusing to allow us to carry anything other than our small rucksacks. As the door swung open to our room, I was reminded of 'Prisoner: Cell Block H'. I tried hard to hide my disquiet, as the students crowded into our quarters, and showed little inclination to leave. When we were finally left alone in our room, I was relieved to be given some time to convalesce. I hoped that the feelings of unease I had would soon subside, as I knew they must do. I was, however, quite amazed by how my impressions of the place had worsened with almost every minute after that first spectacular glimpse from the gate.

A few days later, we all met up again in Colombo. We made our own ways there, which meant travelling by bus. This mode of transport is very much part of everyday life for the greatest majority of Sri Lankan people. For the uninitiated, however, it can be quite a shock. Buses are often in a fairly bad state of repair - it is common to be able to see the road through the worn wooden floorboards. It is usual, also, for there to be as many standing passengers as seated ones, or frequently more. In the incredible heat and humidity, and therefore perspiring profusely, and standing squeezed between wisened Sri Lankans, whose ability to make their way through a tightly packed crowd would probably qualify them for an international rugby team, I found the first few bus journeys a bit of an ordeal.

We greatly enjoyed meeting up again, and exchanging horror stories of our first experiences of our projects. We attended a week-long course at the headquarters of the organisation which runs Batangala and one of the other projects, the National Youth Services Council. During this week, we were given several lessons on Sinhala, the language spoken most commonly in the South and West of the island. Some foundations of knowledge of Sinhala were laid thus, although most of us only really became able to communicate in the language after several months of practice.

Having spent the first few days in Colombo longing to get to our projects, we now found ourselves somewhat dreading our return to them. However, return we did. As the centre became more familiar, I began to feel more comfortable there. Apart from my continuing terror of meal times, I was quite pleased to get back and feel like our 'year' was getting properly underway.

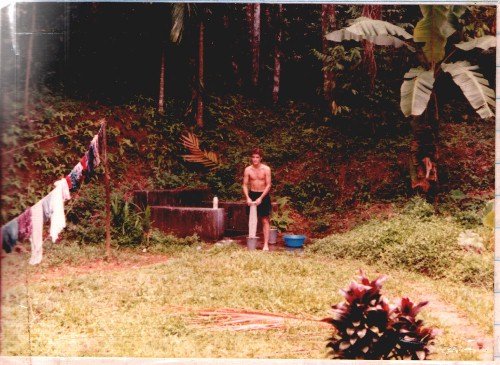

As we had not washed a single item of our clothing since we left Britain, we now had a reasonable collection of dirty laundry. Our first attempts at hand washing, at the well outside the bungalow we shared with Mr Jayasiri (Smiler) and his family, along with three other male members of staff, were not entirely successful. It also became apparent that it was not entirely prudent to accumulate dirty washing until you have to wash all of your clothes at once. When I had stood in the roasting sunshine for a few hours, scrubbing at my t-shirts and socks, I felt a new appreciation for that wonderful appliance, the washing machine! There is certainly no need for a dryer machine, however, as the sun's ferocity dries clothes to crispness in an hour or so. If it were not for the expert advice from the female members of Mr Jayasiri's family - his wife and sister-in-law, it would have been some time before we were able to get clothes passably clean.

Me attempting to wash various items of clothing at the well during our first weeks.

Washing ourselves was done by much the same method. Our bathroom, which we shared with a neighbour, consisted of a large tub, which periodically filled with cold water, and a toilet which has to be flushed with buckets from the aforementioned tub. Even in the heat which we were still not accustomed to, tipping buckets of cold water over your head in the morning leaves you in no doubt as to the fact that you are most definitely awake!

During our first few weeks at Batangala, we were woken every morning very early by a few students offering us cups of tea. The first time this happened, I was struck by what a pleasant idea it seemed. Sri Lankans, however, drink tea in a way I was somewhat unaccustomed to. The mix of sugar, milk powder and perhaps a little tea in there somewhere, that the students poured out for us, came as a bit of a surprise. After that first cup, we politely refused the offers made so persistently in the mornings.

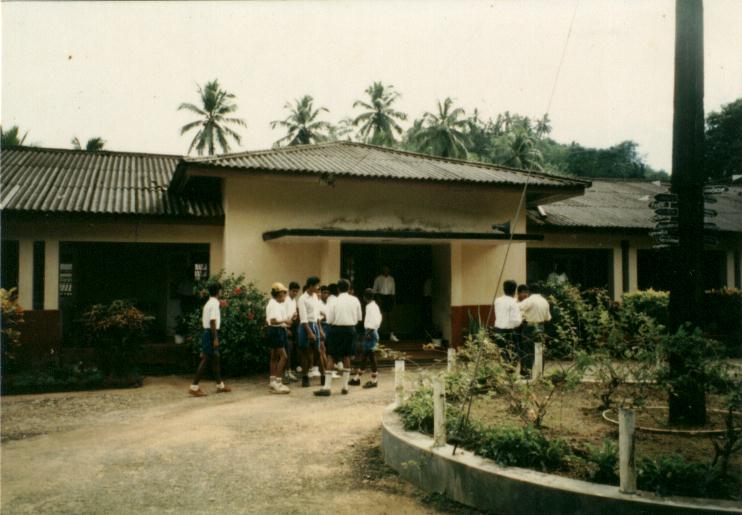

Before we actually got into the classroom with the students, we were a considerable source of curiosity to them. It is true in general in Sri Lanka that foreigners, and particularly 'sudus' (whites), attract a fair degree of attention. Being stared at constantly took some getting used to. It was particularly unsettling at times around the centre, where we felt annoyed that we could not walk around our own 'home' without being scrutinised. We were also struck by how old the students seemed. Information about the project, given to us beforehand, had stated the age of the students as being betwixt 16 and 23 years.Contemplating our soon-to-be class members, however, I could see few who seemed younger than us. Although this shouldn't have surprised me, it was a little intimidating.

I was quite anxious when the time came to teach the first lesson. We were given a timetable, and no further guidance as to our duties. So, with a few notes by means of preparation, we set out to begin our lessons. It was quite difficult to know what level to pitch the classes at, as we had little idea of what the students had already learned, and what they would expect to be taught.

My first few lessons went far from smoothly, but neither were they complete disasters. One thing I did find very difficult to do was improvise; once my planned activities had been exhausted, I was somewhat at a loss. It was not long, however, before these moments of panic became infrequent. The students were normally polite and respectful, and discipline was not really a problem. In the first few weeks, with a very limited knowledge of Sinhala, I did at times find communicating my ideas and intentions to the class a little arduous. Again this rapidly improved, as I got better at explaining things using gesticulation, and picked up a few useful words of Sinhala, and the students came to understand my strange blend of English, Sinhala, and hopping around.

We ventured a little out of the centre, and were shown around parts of it such as the agriculture section across the road from the main classrooms and hostels. The centre is set in the foothills about half way between Kandy and Colombo, and the scenery is quite beautiful. The climate, while not like that of the cooler and wetter hill country, is somewhat less fierce than nearer the coastal regions to the West. We were not convinced when the NYSC driver who dropped us off told us "Batangala is cold; like England", but at times it was pleasantly cooler than the heat we had at first experienced in Colombo. We arrived during the last of the two yearly rainy seasons of 1995, and the incredibly heavy rain which came daily in our first few months brought the temperature down considerably. With the lush jungle-like vegetation surrounding Batangala, however, the rain created some very humid spells. As the sun evaporated the moisture left by the downpours, the hills overlooking the centre were often shrouded in a pretty blue-tinted mist in the mornings.

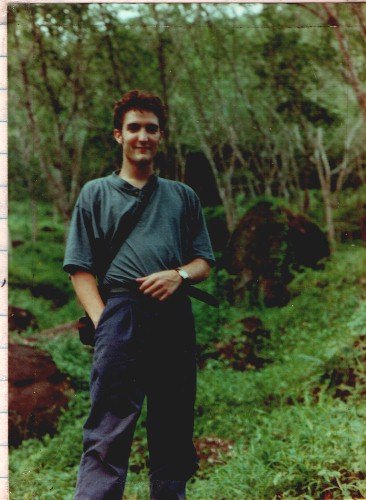

On one afternoon which Giles and I had free, we decided to attempt to scale one of the hills adjacent to our bungalow. This hill was covered in tapped rubber trees and large rocky outcrops. One of these outcrops, which is clearly visible for some distance around the centre, gives it its name. 'Gala' is Sinhala for rock, as we deduced when several people had pointed at the hill saying 'BatanGALA'.

An intrepid explorer ascending the Batangala hill.

We got most of the way up the hill, when I noticed a slight stinging coming from my leg. I soon realised I had acquired my first leech. It was only small, but was growing rapidly. We descended with some haste, and I removed the parasite, taking care not to leave its teeth in the wound, as this is a good way of getting a nasty infected sore. We were gradually getting used to Batangala.